Industrialised shipping may be leading to a large number of whale shark deaths across the world, according to a new study.

Marine biologists from the Marine Biological Association (MBA) and the University of Southampton have led ground-breaking research which indicates that lethal collisions of whale sharks with large ships are vastly underestimated, and could be the reason why populations are falling.

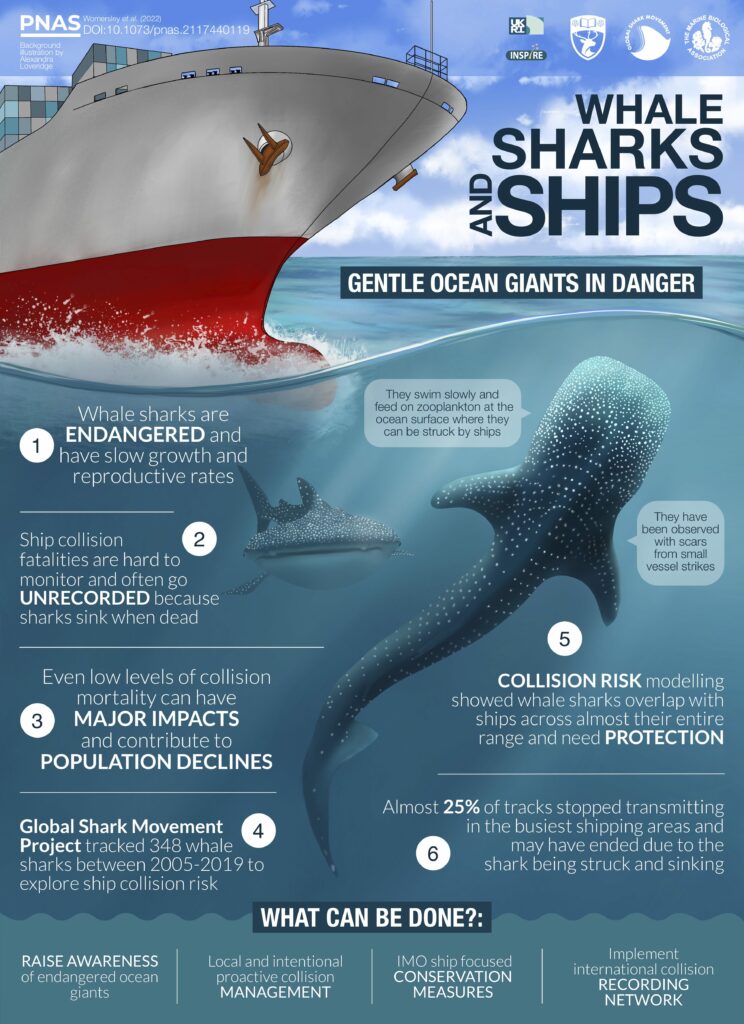

Whale shark numbers have been declining in recent years in many locations, but it is not entirely clear why this is happening.

Because whale sharks spend a large amount of time in surface waters and gather in coastal regions, experts theorised that collisions with ships could be causing substantial whale shark deaths; but there was previously no way of monitoring this threat.

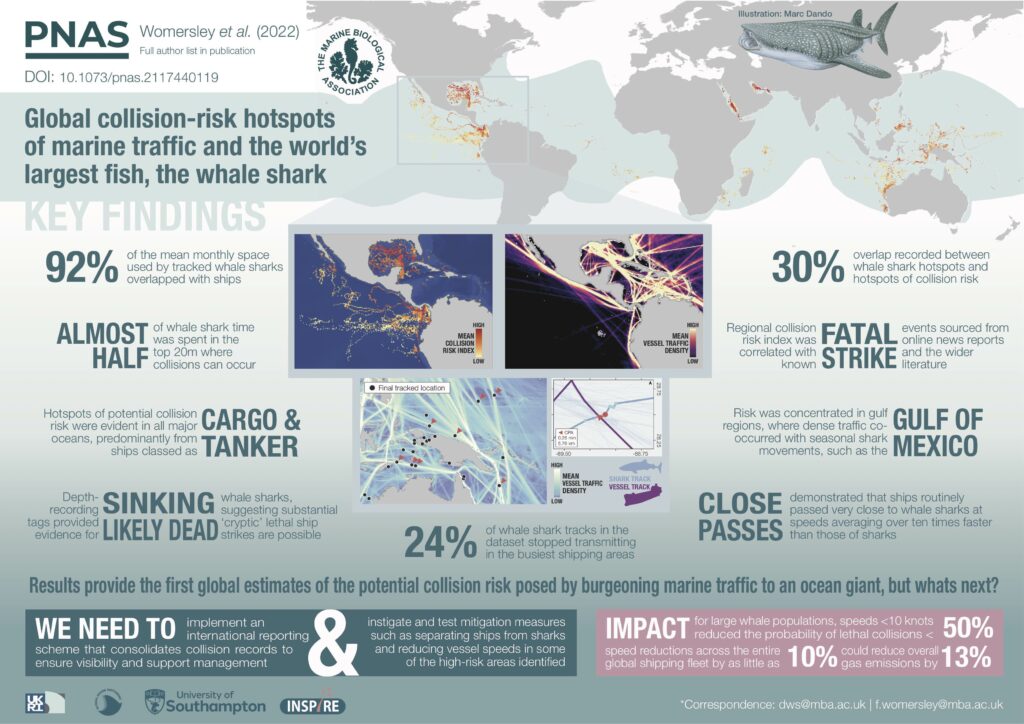

Scientists from 50 international research institutions and universities tracked the movements of both whale sharks and ships across the globe to identify areas of risk and possible collisions. Satellite tracked movement data from nearly 350 whale sharks was submitted into the Global Shark Movement Project, led by researchers from the MBA.

The team mapped shark ‘hotspots’ which overlapped with global fleets of cargo, tanker, passenger, and fishing vessels – the types of large ships capable of striking and killing a whale shark – to reveal that over 90 per cent of whale shark movements fell under the footprint of shipping activity. The study also showed that whale shark tag transmissions were ending more often in busy shipping lanes than expected, even when they ruled out technical failures. The team concluded that loss of transmissions was likely due to whale sharks being struck, killed and sinking to the ocean floor.

The study also showed that whale shark tag transmissions were ending more often in busy shipping lanes than expected, even when they ruled out technical failures. The team concluded that loss of transmissions was likely due to whale sharks being struck, killed and sinking to the ocean floor.

University of Southampton PhD Researcher Freya Womersley, who led the study as part of the Global Shark Movement Project said: “The maritime shipping industry that allows us to source a variety of everyday products from all over the world, may be causing the decline of whale sharks, which are a hugely important species in our oceans.”

Whale sharks are slow-moving ocean giants which can grow up to 20m in length and feed on microscopic animals called zooplankton. Whale sharks help regulate the ocean’s plankton levels and play an important role in the marine food web and healthy ocean ecosystems.

Professor David Sims, Senior Research Fellow at the MBA and University of Southampton and founder of the Global Shark Movement Project said: “Incredibly, some of the tags recording depth as well as location showed whale sharks moving into shipping lanes and then sinking slowly to the seafloor hundreds of metres below, which is the ’smoking gun’ of a lethal ship strike.”

“It is sad to think that many deaths of these incredible animals have occurred globally due to ships without us even knowing to take preventative measures.” says Sims.

At present there are no international regulations to protect whale sharks against ship collisions. The research team say that this species faces an uncertain future if action is not taken soon. They hope their findings can inform management decisions and protect whale sharks from further population declines in the future.

Womersley said: “Collectively we need to put time and energy into developing strategies to protect this endangered species from commercial shipping now, before it is too late, so that the largest fish on Earth can withstand threats that are predicted to intensify in future, such as changing ocean climates.”

Read the full paper in PNAS.

– Ends –

Womersley, F.C., Humphries, N.E., Queiroz, N., Vedor, M., da Costa, I., Furtado, M., Tyminski, J.P., Abrantes, K., Araujo, G., Bach, S.S., Barnett, A., Berumen, M.L., Bessudo Lion, S., Braun, C.D., Clingham, E., Cochran, J.E.M., de la Parra, R., Diamant, S., Dove, A.D.M., Dudgeon, C.L., Erdmann, M.V., Espinoza, E., Fitzpatrick, R., González Cano, J., Green, J.R., Guzman, H.M., Hardenstine, R., Hasan, A., Házin, F.H.V., Hearn, A.R., Hueter, R.E., Jaidah, M.Y., Labaja, J., Ladino, F., Macena, B.C.L., Morris Jr, J.J., Norman, B.M., Peñaherrera-Palma, C., Pierce, S.J., Quintero, L.M., Ramírez-Macías, D., Reynolds, S.D., Richardson, A.J., Robinson, D.P., Rohner, C.A., Rowat, D.R.L., Sheaves, M., Shivji, M.S., Sianipar, A.B., Skomal, G.B., Soler, G., Syakurachman, I., Thorrold, S.R., Webb D.H., Wetherbee, B.M., White, T.D., Clavelle, T., Kroodsma, D.A., Thums, M., Ferreira, L.C., Meekan, M.G., Arrowsmith, L.M., Lester, E.K., Meyers, M.M., Peel, L.R., Sequeira, A.M.M., Eguíluz, V.M., Duarte, C.M. and Sims, D.W. (2022) Global collision-risk hotspots of marine traffic and the world’s largest fish, the whale shark. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A.119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117440119

Photo credits: Simon Pierce.

Press release published by The Marine Biological Association.

The Marine Biological Association (MBA) is a learned society of scientists and members in 35 countries, across 5 continents. Its in-depth scientific research into the interconnected marine environment is carried out from its prestigious laboratory HQ in Plymouth, UK.

Contacts

Corresponding authors:

Professor David Sims, The Marine Biological Association. Landline: +44 (0)1752 426487. Mobile: +44 (0)7848 028456. Email: dws@mba.ac.uk Twitter: @TheSimsLab

Freya Womersley, The Marine Biological Association. Email: frewom@mba.ac.uk Twitter: @FreyaWomersley

The Global Shark Movement Project

The Global Shark Movement Project (www.globalsharkmovement.org) is a collaborative scientific research project based at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, UK (www.mba.ac.uk), which aims to advance scientific knowledge of shark behaviour, ecology, conservation and fisheries science that can be used to inform improved management of threatened sharks and ocean biodiversity.

Tens of millions of pelagic sharks are harvested each year by high seas fisheries but with little or no management for the majority of species. Sharks are particularly susceptible to the effects of human exploitation due to slow growth rates, late age at maturity and low fecundity, traits making them comparable to marine mammals in terms of vulnerability. Global data on pelagic shark habitat hotspots, spatial patterns of vulnerability in relation to fisheries, and how sharks respond to changing environment are lacking, precluding understanding where in the global ocean conservation needs to be focused. GSMP aims to close this knowledge gap.

May 05, 2022

May 05, 2022